The first time that I experienced panic attacks, I was seventeen, and I felt like I was living in a horror movie. I would be walking down the street in the middle of the day, when suddenly the light would go all funny. The ominous overture to Carl Orff's Carmina Burana would be playing faintly in the background, except I hadn’t heard Carmina Burana before except in scenes depicting hell in movies. The color of everything would be sickly and wrong and I would feel all the blood in my body drain to my feet, and there would be the presence of some sickly grotesque thing that defied the normal order of the world, some dark thing come from the other side to suck me under.

This feeling would overcome me every few minutes, hundreds of times each day, so that life was rather like creeping my way through the hotel in The Shining, or maybe one of those new homemade-looking horror movies whose advertisements celebrate how “disturbing” they are.

The therapist I saw took me to the psychiatrist to see if he would recommend medication. He shot a dismissive glance at my gaunt figure and tattered thrift-store clothing and said, “If this is still happening in six months, we’ll give you some antidepressants.”

Six months, I remember thinking in horror. If this is still happening in six months, I’ll be dead.

Six months later, the attacks weren’t gone, but through weekly therapy, I was learning to control them, so that I could usually anticipate them and stop them before they got really bad. I learned that I needed to get a full night’s sleep and eat reasonable meals and not wallow in stress or immerse myself in bizarre, alienating music and literature, frustrating lessons, but ones that I suppose my body thought it was high time for me to learn.

Other than sedatives, I don’t think anti-anxiety medication had been developed back then. If it was, I certainly wasn’t offered any. Since that time, I have had several other bad bouts of panic attacks, and I have never been offered any sort of medicine by the psychiatric and medical professionals with whom I have consulted.

From the stories that I’ve heard, that you’ve heard, too, I am an anomaly. Friends, books, TV shows, magazines all tell us that psychotropic drugs are dispensed like corn syrup, an efficient solution to our culture’s wealth of mental disorders that avoids the expense of psychological treatment while providing easy revenue to the drug companies. At times, I have felt cheated—why haven’t they offered me any of these “overprescribed” drugs? Am I not screwed up enough to warrant a healthy dose of that Prozac they’re debating in all the magazines, that Paxil and Zanex that they seem to be prescribing for everyone else I know?

I especially feel cheated when I think of that horribly suffering teenager I once was, and wonder: couldn’t they have given me something? Surely there must have been something, some sedative, some kind of valium or Quaalude or horse tranquilizer that could have calmed down my overactive brain, rather than leaving me to pull myself, with grasping bloody fingers and a year of therapy, up out of that horror movie and into some kind of sane, properly-ordered mental functioning.

On the other hand, when I watch the struggles of the many people I know who have been placed on medication, I feel like I got out easy, relieved and lucky to have not been pulled into a deeper kind of morass—the engulfing cycle of being on medication and getting off of it.

I’ve watched a lot of people try to go off of their medication, and from what I’ve seen, the process of going off of medication for mental illness will in itself make a person mentally ill. I’ve watched some of the closest people in my life shake and cry and wail that they need the medicine, with all the desperation of heroin addicts. I’ve watched people adjust the dosage—just a little more now, now a little less, cut down by half, and if you completely freak out, go back up by a quarter. One friend who struggled with her romantic life went to her primary care physician to get referred to a therapist, and instead got prescribed Prozac; a year later, her struggle was not to maintain a healthy relationship but to get off the Prozac.

Of course, one obvious explanation for the anguish caused by going off medication is that the medication is needed, and that it is the only thing that was preventing the suffering in the first place. Your brain is like any other organ, and if your brain is sick, you may require medicine for the rest of your life, just as you would if you suffered from thyroid or heart disease.

This may be the case for some mentally ill people, but as far as I understand, it is impossible to diagnose conclusively who they are. There is no physical test to diagnose mental illnesses; they are diagnosed by symptom. It is as though I went to the doctor complaining of fatigue and thirst and, based on those complaints, I was assumed to have diabetes and put on a regimen of insulin. If my symptoms abated in a few months, it might be difficult to tell if this was due to the insulin or something else altogether. The only way to tell would be for me to stop taking the insulin, and see if I felt sick again. Except, since my body is accustomed to the insulin, I may feel faint and ill when I stop taking it, and this could be a normal sign of withdrawal, or a deadly symptom of my now-untreated illness, and it may only be my death that provides a conclusive answer.

I don’t mean to insult psychiatry as an imprecise science. I have seen many people I care about treated with drugs that seem to have saved their lives, and I will always be an avid supporter of anybody’s right to stay on a medication that is preventing them from being miserable, numb, non-functional, or delusional. I know firsthand what mental illness can be, and if the path to my own health lay in a pill, I would take it without hesitation.

A few weeks ago, on the second anniversary of the death of David Foster Wallace, I heard several radio programs discussing his life, his writing, and his battle with depression. Wallace had done something that I have seen so many people I care about do: he reached a happy, stable time in his life, and, no longer suffering the symptoms of his depression, he decided to go off of the medicine that he had taken for years.

The people in my life have done this with varying levels of success. A few people I know have actually managed to go cold turkey, and found that the depression they experienced as young adults seemed to have dissipated with maturity. But more often, my friends and family members have found that their depression returned. They may be able to take lower doses of the antidepressants, but can’t seem to go off of them entirely.

David Foster Wallace’s version of this process sends a chill through anyone who takes antidepressants or cares about somebody who does: when he stopped taking his medication, his depression returned full-force, and when he returned to his medicine, it no longer worked, and he committed suicide.

It’s the fear of this very sort of dependence that leads so many people I know to want to get off medication. What if there is some disaster? I don’t want to be unable to function without medicine. Unlike diabetics and other people who have a diagnosable, physiological need for a medication, people with illnesses like anxiety and depression are never sure just how dependant they really are, nor are their doctors. It’s impossible to find out just how dependant you are on antidepressants without risking your life or your sanity.

Now when I watch people I know try to reduce or go off their medicine, I give grudging thanks to that judgmental psychiatrist who did not want to give me medication when I was a teenager. Without a chemical remedy, I had to figure out how to make my own mind healthy. I learned a lot of skills that I have used throughout stressful times in my life, even times when my panic attacks have returned almost as strongly as the first ones I experienced. I have never had to wonder whether I really need a medication, to feel the temptation to turn to it when times are difficult, to try to distinguish anxiety caused by needing medication from anxiety caused by withdrawing from medication. I don’t believe that everyone’s mental health problems can be solved without medicine, but I will be forever grateful to know that mine can, and to have the tools to do it.

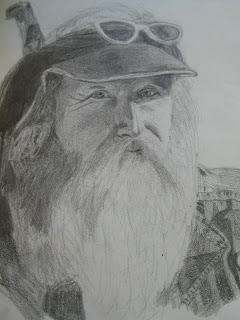

The illustration depicts Berkeley's Hate Man. I don't know if he ever went on or off his meds.